|

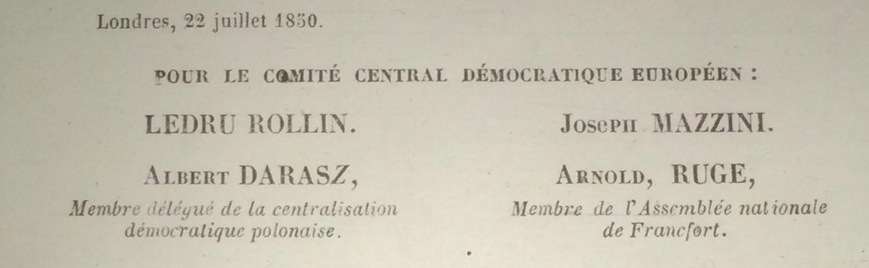

The European Union (EU) often is considered impossible to transform because it is governed by treaties that only can be revised by unanimity. While national politics, despite all the limitations of representative democracy, is an arena in which competition is arbitrated through universal suffrage, European politics often is perceived as being totally out of citizens’ control, governed through elitist, and often confidential, negotiations that are insensitive to the public’s discontent and aspirations. Are there only two choices––accept the EU as is or leave it? First, this reasoning ignores democracy’s historical dynamics. The fact that a regime protects the status quo through formal rules never has prevented a democratic revolution. The authoritarian monarchies of the 18th and 19th centuries were much more conservative than today’s EU. Nevertheless, they have been transformed. The history of democracy is the history of its conquests, of its emergence where it was least expected. Second, this reasoning does not reflect the reality of European politics. No, the EU is not blocked by the unanimity rule. Throughout its history, governments have invented many ways to overcome this obstacle and elicit reforms despite a reluctant minority: - Compromise. If all member states had to agree on everything every time they drafted or revised a treaty, European integration would never have even started. Major advances were rarely consensual, but were made possible through transactions between states. - Threatening the minority with marginalisation. This is what happened in the case of the 1986 European Single Act. Margaret Thatcher's UK (as well as Denmark and Greece) voted against the opening of negotiations to revise the Treaty of Rome, but eventually joined the negotiations out of fear of being left behind while other member states moved forward. - Differentiated integration. The euro, Schengen and defence cooperation are policies that some states chose not to embrace from the outset, but did not prevent other member states from adopting them. - Replacing treaty revision with an intergovernmental agreement between some member states only. This was done for the 2012 European Fiscal Compact, adopted by 25 states, but rejected by the UK and Czech Republic. If these strategies could serve the objectives of yesterday’s elites, why should they not serve the democratic aspirations of today’s citizens? Furthermore, it is possible to reform the EU and increase citizens' power without needing to revise treaties simply by reforming some member states’ practices. For example, this is how the US presidential election became democratic. Indeed, the US Constitution leaves each state free to decide how to appoint the electors who vote for US president. Originally, most states chose them through their legislatures. The practice of choosing them via popular election became progressively widespread during the 19th century. This evolution was not the result of a constitutional amendment, but of state-level reforms. Similarly, an EU member state today could declare: ‘On this important issue, the position we will defend in the EU Council will depend on the mandate our citizens will give us by referendum’. As for the appointment of the European Commission’s president, which currently is accomplished through negotiations between national leaders and members of the European Parliament, a member state could commit itself to consulting its citizens on their preferred candidate before taking a position. If these practices were to spread, even to a few member states, the nature of concerned EU decisions would change radically. Therefore, the formal problem of unanimity largely is overestimated. However, a political problem remains. If the democratisation of practices affects only one member state, citizens’ voices will not make a decisive impact. The Greeks experienced this bitterly after the July 2015 debt referendum. A large majority of Greek citizens voted against the agreement that the EU proposed, but Greece, nevertheless, found itself too isolated to be able to oppose the united front of all the other member states and eventually gave in. Therefore, it is not necessarily enough for citizens to have their say. They must have it in a sufficient number of member states so that their voices cannot be ignored. Here again, political elites already have demonstrated that it is perfectly possible to transform the EU's political system by aggregating national mobilisations. This is how the European Parliament initially was empowered. Indeed, the European Parliament originally only had consultative power. How did it become a key player in EU decision making? Beginning in the 1960s, it benefited from the mobilisation of national parliaments, which pressured their respective national governments through the following message: ‘The parliamentary powers we exercise at a national level should also be exercised at the European level; that is why we will only ratify the treaties you have negotiated if they include provisions strengthening the European Parliament’. The German, Dutch and Italian Parliaments in particular have been at the forefront of this fight, and parliaments exercised pressure in enough member states for governments to be obliged to consider their demands. Could citizens do in the future what parliamentarians did in the past? Can we imagine that one day, the governments of a significant number of member states will arrive in Brussels and say to their counterparts: ‘My citizens are demanding strong measures in favour of EU-level democracy, such as the popular election of the Commission or the creation of a European referendum on popular initiative. I cannot agree on anything if I do not have guarantees on these points’? In other words, is it conceivable for a coalition of simultaneous popular mobilisations in favour of democracy to be formed in Europe? To answer this question, we need not probe the future; it is the past that we must examine. A European revolution is possible because it already happened. In the 19th century, Europe was governed by authoritarian monarchies. In 1815, these monarchs formed the Holy Alliance, with the objective of protecting each other against future revolutions. However, in 1848, in almost all parts of Europe, with the notable exceptions of Russia and the UK, people simultaneously rose up to demand democratic reforms. The chronology of the first few months speaks for itself: - January: revolt in Sicily, then in southern Italy - 24 February: barricades in Paris and proclamation of the Republic - 4 March: uprising in Munich - 13 March: uprising in Vienna - 15 March: uprising in Budapest - 17 March: uprisings in Venice and Krakow - 18 March: uprisings in Milan and Berlin - 21 March: mass demonstration in Copenhagen - 24 March: riots in Amsterdam All over Europe, people protested, demonstrated, waved tricolour flags, created assemblies, voted, drafted constitutions, signed petitions and founded free newspapers and political clubs. Contemporary actors were fully aware that they were participating in a European movement. The news of uprisings in other countries often was celebrated. The French February revolution kicked off the mobilisation in Germany. In May, a demonstration was held in Paris in support of Polish revolutionaries. In June, young Romanians who had fought on the Parisian barricades sparked a revolution in their own country. When reactionary forces hit the continent, the democrats did not forget the European nature of their struggle. In July 1850, revolutionaries exiled in London created the European Democratic Central Committee. Members included Alexandre Ledru-Rollin, who had been Minister of the Interior in the French 1848 provisional government; Giuseppe Mazzini, who had founded the Young Europe movement in the 1830s and had been one of the leaders of the Roman republic established in 1849; Arnold Ruge, the main spokesman of the democratic party in the German Frankfurt Parliament, founded in May 1848; and Wojciech Darasz, who represented Polish democrats. In the face of the Holy Alliance of monarchs, these men called for the formation of a ‘Holy Alliance of People’, the union of European democratic parties and the reorganisation of Europe by a congress of representatives from all nations. For them, ‘European democracy’ was based on brotherhood among nations against the ‘League of Kings’. Unfortunately, the regimes put in place during the 1848 revolution generally were short-lived, and the European Democratic Central Committee’s hopes were not fulfilled. European brotherhood soon gave way to rivalries and wars.

And yet, how can we not be struck by this precedent? A European democratic revolution was possible during the days of assertive nationalism and horse-drawn carriages, but we are told that it would be impossible in today's EU? How can we not see the current relevance of this struggle by pro-democracy citizens, both against the elites who sought to suppress their voices and against ethnocentric chauvinism that weakened them by pitting nations against each other? The 1848 revolution reveals a truth that has been repressed from national memories. No, democracy was not born within isolated and inward-looking nations that the EU would now artificially link to each other. Quite the contrary! National democracies were born and took their first steps in the context of a European movement. The precursors who fought during the heroic age––when shouting ‘Long live democracy!’ could cost you your life––spent their time crossing borders, circulating ideas, drawing inspiration from their neighbours, embracing foreign causes and hoping for a continent-wide victory. Reactivating the European revolution’s rhetoric today does not mean weakening national democracies; it means reminding them of their origin, of their baptism. Sometimes, remembering leads to action. Remember, Europe! Comments are closed.

|

My name is Pierre Haroche and I am a specialist in European integration and European security.

In this blog I present my thoughts on EU democracy, defence and identity. If you are interested in my proposals, do not hesitate to get in touch! |

Proudly powered by Weebly