|

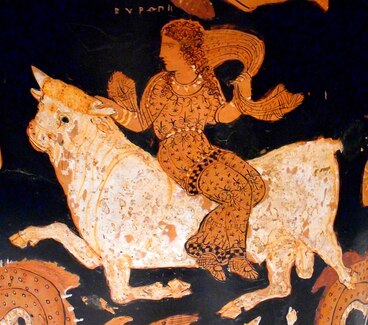

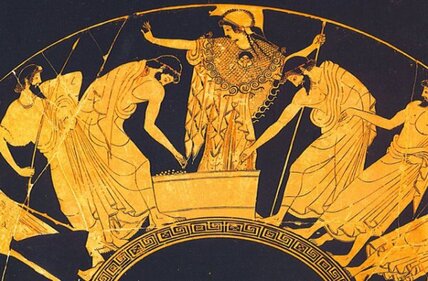

Democracy and Europe are two sister ideas. Both were born in Greece, around the 6th century BC. Both developed in the classical period, marked by the geopolitical opposition between the Europe of Greek cities and the Asia of the Persian ‘Great King’. We should remember this historical connection. It is now more vital than ever to reactivate it. According to Aristotle, the first democratic reforms were introduced in Athens by Solon, an archon, in 594. But Athenian democracy really took off in the middle of the 5th century BC with Pericles’ reforms. The oldest known text using the term ‘democracy’ dates from this period. The Histories of Herodotus tell us that at the end of the 6th century BC, Greek cities in Asia Minor debated the possibility of rebelling against the domination of King Darius of Persia. Histiaeus, the tyrant of Miletus, rejected the idea. According to him, without Persian support, all of the region’s tyrants would end up overthrown because all cities ‘prefer democracy to tyranny’. The oldest known text using the word ‘Europe’ to designate a geographical space is a hymn to Pythian Apollo. This text, which probably dates from the 590s BC, tells how Apollo founded the sanctuary of Delphi and, when turned into a dolphin, attracted Cretan sailors to become its guardians. The god predicted that ‘they who dwell in rich Peloponnesus and the men of Europe and from all the wave-washed isles’ would come to seek his oracles. As we can see, ‘Europe’ here refers only to the continental part of Greece. In the 5th century BC, however, the term had its modern meaning as one of the main parts of the world. In Herodotus, the world is divided between Asia, dominated by Persia, and Europe, represented by Greece. Also, Europe and democracy both have their own Greek myth. Europe was a princess of Tyre in Phoenicia whom Zeus, turned into a bull, kidnapped and brought to the shores of Crete. Herodotus proposes a less enchanted version of this story: Cretans allegedly kidnapped the princess, and this crime, like Helen’s later abduction by the Trojans, would be one of the episodes in the origin of the wars between Europe and Asia (that is, between Greeks and Persians). As for democracy, its myth is told to us by Protagoras. According to him, the first men lived in isolation and were unable to resist wild animals’ attacks. Ignoring the art of government, they could not unite in cities without harming each other and dividing again. Fearing the annihilation of mankind, Zeus then sent Hermes to offer men αἰδώς (respect) and δίκη (justice). Hermes then asked if these gifts should be given to all men or to only a few. Zeus replied that they should be distributed to all men, otherwise no city would survive. According to Protagoras, this story explains that when it comes to giving an opinion on an ordinary art such as medicine or architecture, only a small number of specialists are competent. But when it comes to the art of government, all men are competent and must be able to give their opinion. In other words, government should not be restricted to an elite of experts and should be open to all. What remains today of this millenary link between Europe and democracy, these two gifts of Zeus? At a time when the institutions of the European Union (EU) are often viewed with suspicion by people who see them as elitist arenas beyond the reach of ordinary citizens’ influence, a healthy return to the roots is needed. Some might argue that European democracy already exists. The key decision-makers in Brussels are national governments, which meet in the EU Council, and directly elected members of the European Parliament (MEP). However, after the election stage, the European political system tends to keep citizens away from the decision-making through elitist and confidential compromises. For example, MEPs are elected on the list and platform of their national party. But when they arrive in the European Parliament, their national party must join a European party made up of national delegations with sometimes very different preferences. They therefore make compromises. Then, since no single European party has a majority, they do deals with one another, forming broad coalitions involving the right, left and centre. Finally, the majority of the European Parliament has to find compromises with the EU Council in order to adopt new legislation. In the end, what remains of citizens’ influence? Not much. Delegating decision to an elected representative is one thing. But after a chain of cascading delegations where each step dilutes the initial mandate into increasingly opaque compromises, voters simply lose control. As a result, they tend to perceive EU decisions as arbitrary, without really knowing whom to hold accountable. When they are dissatisfied, because they do not know which elected official, party or government to sanction, they simply reject the system, the EU itself. In other words, we have reached a stage in history where the link between Europe and democracy is once again crucial. European unity will not survive without the support of the people. And this support can only be achieved through a genuine European democratic revolution. If, 2,500 years ago, the Greek democratic ideal largely inspired the birth of European identity, we must now restore this ideal to save Europe from dilution. What do the ancient Greeks tell us? That democracy is much more than a formal mechanism in which decision-makers are selected through elections, as is still often claimed. In a much more ambitious sense, it is the participation of all in decision-making, without any distinction, even on the basis of expertise. According to Herodotus, when the people rule, ‘places are given by lot, the magistrate is answerable for what he does, and measures rest with the commonalty’. In his founding myth, Protagoras sounds prophetic: if a city government can rely on only a small elite of specialists, the city will collapse and men will go back to division and weakness. This warning seems to be addressed directly to today’s EU. If it can rely on only a handful of Brussels technocrats, it will collapse, sooner or later. Here is a proposal. For decades, MEPs have complained that they are working between two cities, at the cost of wasted time and public money: Strasbourg, which is the European Parliament’s official seat, and Brussels, where, for practical reasons of proximity with other European institutions, they spend most of their time. The simple solution would be to officially relocate the European Parliament to Brussels. But what would we then do with Strasbourg, this symbol of reconciliation to which many Europeans are very much attached? Why not make Strasbourg not a parliamentary capital but a democratic one? The current seat of the European Parliament would become the seat of a new European Citizens’ Assembly. Ordinary citizens, regularly drawn by lot in all EU states, would meet there to express their voices directly, without the intermediation of parties and elected representatives. On certain long-term issues, such as trade or climate agreements, or on controversial subjects on which national parliaments have expressed disagreement, the European Commission would be obliged, before presenting a text, to have it validated by the Citizens’ Assembly, thus proving that it is in line with Europe’s general interest. Above all, this European Citizens’ Assembly would work as an interface between European institutions and citizens’ initiatives. Petitions could be sent to the Assembly, and it would have the power to organize referendums throughout the EU, which would be decided by a double majority of voters and states. The Citizens’ Assembly’s internal composition would illustrate the principle that European politics is not the monopoly of an elite. With its ability to receive and support referendum requests, it would also offer every European citizen the possibility of bypassing the long chains of representation that keep them away from EU decision-making. Finally, by bringing together citizens of all nationalities, origins and backgrounds in a single place to make joint decisions, it would symbolically offer a living image of European unity. All that would remain is to inscribe on the Assembly’s pediment the two principles in which the ancient Greeks saw the basis for both equality among men and the cohesion of their union: ΑΙΔΩΣ ΚΑΙ ΔΙΚΗ. Respect and justice. The city of Europeans remains to be built. Comments are closed.

|

My name is Pierre Haroche and I am a specialist in European integration and European security.

In this blog I present my thoughts on EU democracy, defence and identity. If you are interested in my proposals, do not hesitate to get in touch! |

Proudly powered by Weebly